Translation, Then and Now

Considering the impact of translation on the evolution of literature ExploreLorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Duis pharetra pharetra justo tempor blandit. Curabitur velit nisl, malesuada vel rutrum id, viverra in lorem. Aenean consectetur, leo ac porta volutpat, dolor eros pharetra est, vel sagittis arcu enim et sem. In id elit auctor orci scelerisque cursus non ut odio. Maecenas finibus, ligula eget fermentum pellentesque, enim velit mollis ipsum, in rutrum erat nisi eu felis. Morbi non leo dolor. Vestibulum eros lorem, cursus id velit non, aliquet gravida odio.

Reflections on Sagawa Chika’s James Joyce translation

by Fujii SadakazuOn Translation, Little Magazines, and the Eccentricity of World Literature

The Para-Canon of Sagawa Chika’s Translations

Sagawa Chika was a translator, too.

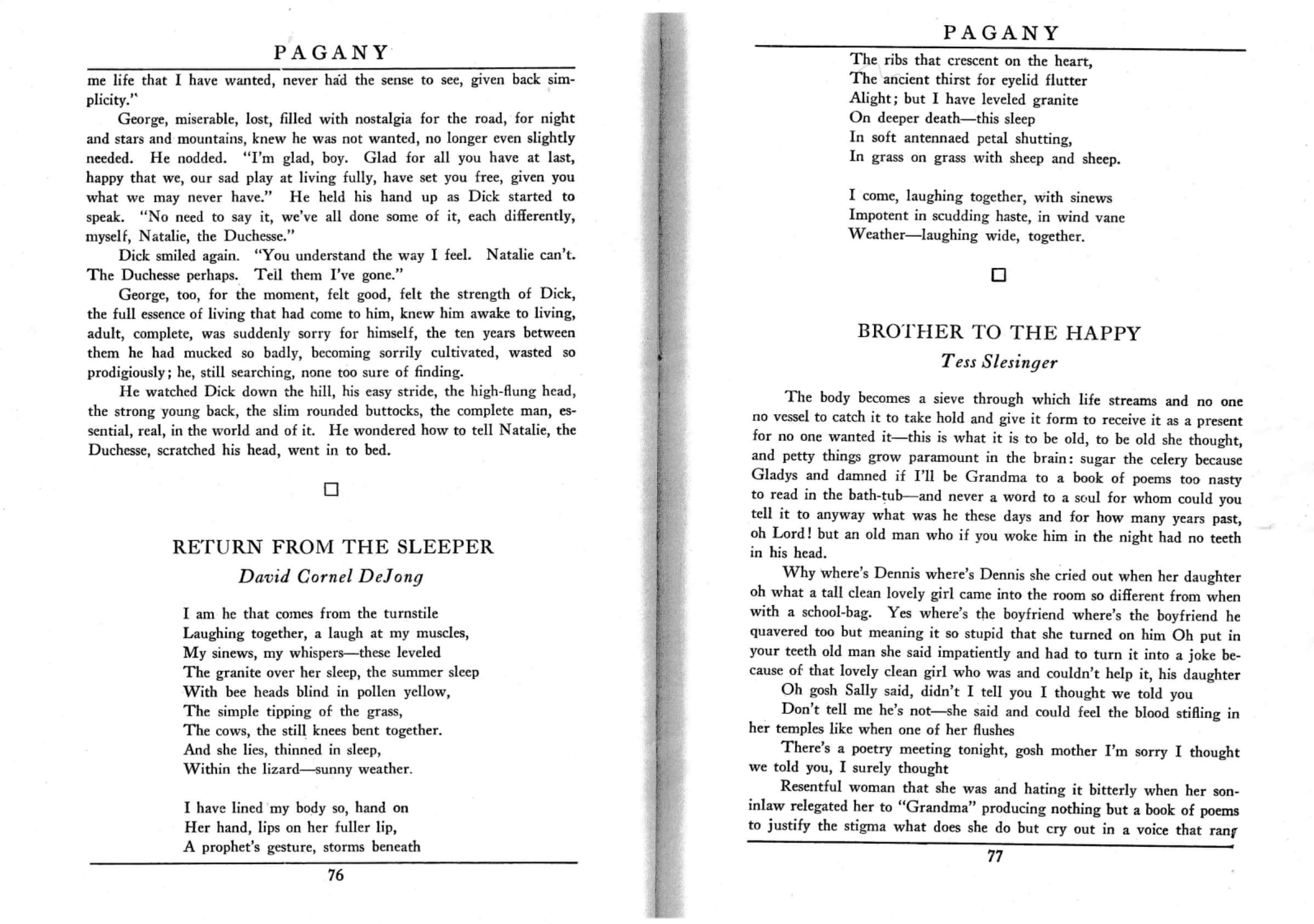

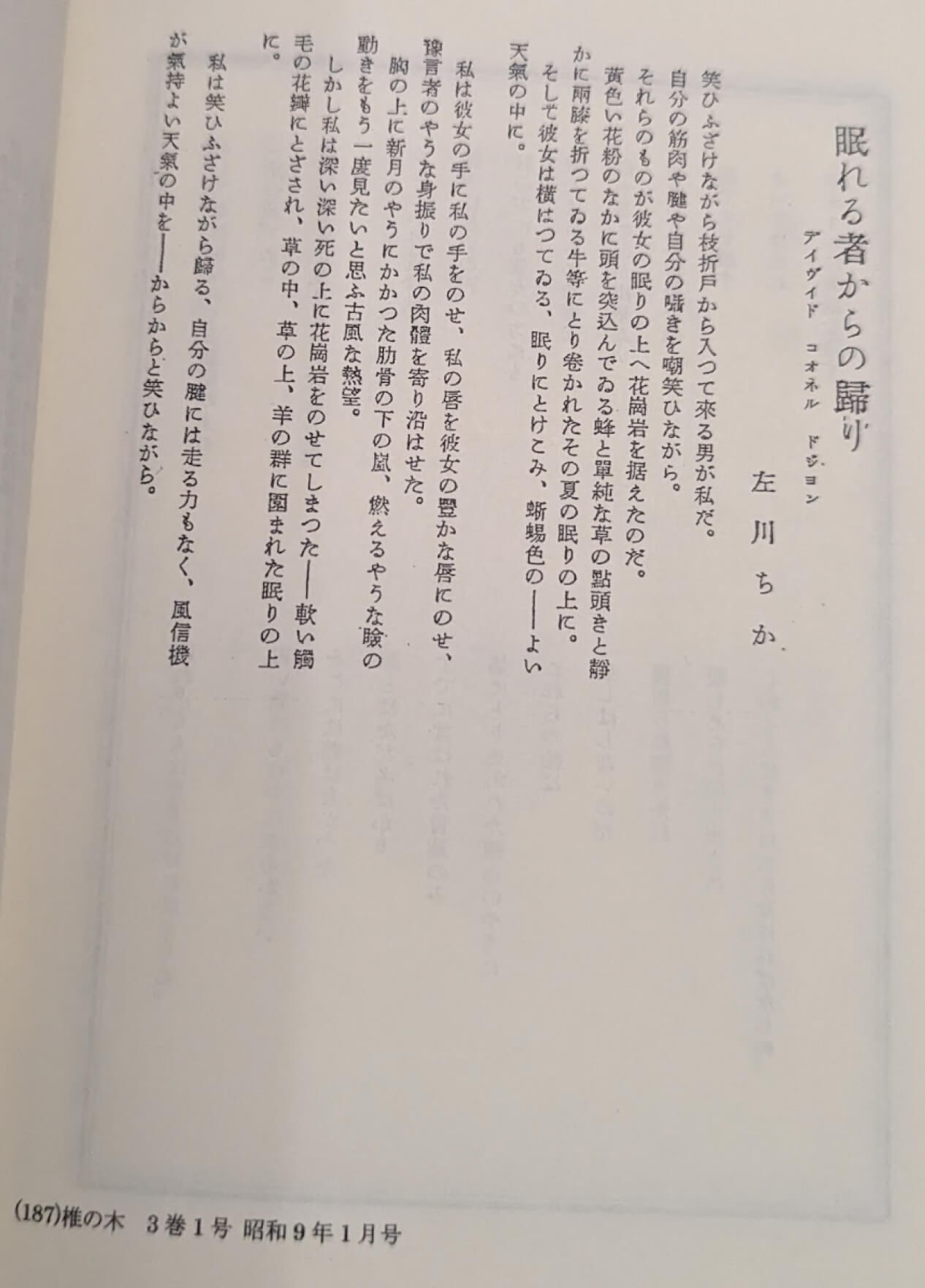

In 2011, a collection of Chika Sagawa’s translations—mostly her translations of poetry—was issued as a slim volume. Its table of contents is striking for what now reads as its idiosyncrasy. It encompasses James Joyce’s sole poetry collection, Chamber Music, in its entirety; selections from Harry Crosby’s 1929 collection, Sleeping Together; and an apparently fairly miscellaneous selection of other uncollected poetry by Charles Reznikoff, Bravig Imbs, Mina Loy, David Cornel DeJong, Howard Weeks, Ralph Cheever Dunning, and R. S. Fitzgerald, plus a prose piece by Herbert Read. Ryu Shimada, in an impressive and detailed scholarly survey of Sagawa’s translations, has recently shown that she also published an additional translated poem by Norman Macleod, as well as an array of short fiction and essays in translation by authors such as Virginia Woolf, Ferenc Mólnar, Aldous Huxley, Sherwood Anderson, Ernest Jones, Norman Bel Geddes, John Cheever, and Frances Fletcher (for the sake of space, I will largely leave these prose translations aside in my discussion here, though this is itself an eccentric and intriguing selection, about which much can be said). Even or especially to those of us who think we know American or Anglophone modernism, this list seems perhaps uneven, maybe surprising, certainly not quite what we would expect. The poets Sagawa translated swerve unpredictably from the hyper-canonical (Joyce), to the well-respected (Reznikoff, Loy), to the virtually forgotten (Weeks, DeJong, Fitzgerald, even Crosby).

I am tempted, surveying this list, and focusing particularly on the poetry, to say something like, “Chika Sagawa was influenced by American modernism,” and clearly this is a true statement, something I could defend full-throatedly with the evidence from this table of contents and her own body of writing. After all, the clear majority of the poets Sagawa translated—all but the Irish Joyce—are American, and the lines between these writers and her own poetry are easily established. But what we might otherwise miss in this claim is how imprecise a term like “American modernism” can be. This list of names—some predictable to me, others completely unknown—reveals that Chika Sagawa’s American modernism touches my own understanding of the category only as a tangent touches a circle. It likewise bears only a passing resemblance to anything I would imagine appearing on a course of that title today, wherever it was taught.